Cattle Drive

Updated: January 28,2026

In the years from 1866 to 1890 the Great Plains of the American West were home to over five million cattle. The cattle survived on the "open range" or public domain lands of Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Montana. Cattle trails went from western Texas northward, through Indian Territory, to the Great Plains of Montana.

At the end of the Civil War there was a shortage of beef in the North. With the South in ruins, Texas was the only source of cattle. Cowboys rounded up, branded, and drove wild longhorn cattle north to Kansas for shipment to the Northeast, and on to Montana where the boundless open spaces and vast grasslands of the eastern plains served as pastureland for the animals. At the time "Cow country" was all but free from farmers with their barbwire fences and grass-eating sheep.

The trail boss searched for places where the cattle could graze and be watered. River crossings, storms, and stampedes were just a few of the dangers cowboys faced on a trail drive. At night, the men took turns riding around the herd, two men at a time, moving in opposite directions. They sang as they went, and though their music may not have been pleasing to the human ear, it was soothing for the cattle. It kept them from getting spooked and stampeding.

Many old traditional western songs were said to be centuries old sea chanteys with new words appropriate for the American West. In the autumn cowboys rounded up the cattle, including strays, from the open range and branded those not already branded. In the spring they cutout the cows ready for market and drove them to the nearest railroad town, often hundreds of miles away. There the cattle were sold to eastern buyers and the cowboys enjoyed a brief period of relaxation before returning home to begin the routine of another year.

On roundups and trail drives, cowboys slept outdoors for weeks at a time. Their bedroll often consisted of a pair of blankets rolled in a piece of oiled, waterproof canvass. Inside his bedroll, he kept extra clothes, letters, and other personal items. The bedroll was the cowboy's personal bedroom on the prairie. At night the cowboys told stories around the campfire or listened to fiddle or harmonica music. Wake up time was often four o'clock in the morning. Each morning the cowboy had to make his bed and load it on the chuck wagon, or the cook might leave it behind. The chuck wagon moved ahead of the herd to the night's camp. Meals for the cowboys came twice a day, once before dawn and again after dark. The men said they had two suppers. Cowboys ate a lot of beans, biscuits, rice, dried fruit, and beef but almost no fresh vegetables, eggs, or milk.

The Longhorns thrived on the open range and the government banned the fencing of lands but the severe winter of 1886 to 1887 virtually wiped out the herds. Many of the once-profitable cattle companies were ruined as hundreds of thousands of cattle perished in the heavy snow and frigid temperatures. The industry never recovered. As cattle raising dwindled homesteaders began pouring into the plains country to fence the land, bust the sod and grow grain on dry land.

The open range was transformed into farms and cattlemen began to settle on ranches with barbwire boundaries. While genuine cowboys remained to work the ranches of Montana the cowboy legend, typified by the reserved, self-reliant hero of the west, has grown in American folklore from the dime-store novels, of the early twentieth century to the modern motion picture hero.

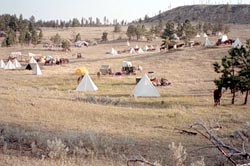

Today, travelers can experience the adventure and true **romance** of the American West on a Montana cattle drive or working ranch vacation, offered at select guest and working ranches across the state. Many ranch stays run three to seven days and give guests the chance to ride daily, help move cattle, and learn practical ranch skills under the guidance of experienced cowboys and wranglers.

On a cattle-drive style week, you may help move several hundred head of cattle between pastures or to seasonal grazing, often spending five to six hours a day in the saddle while the herd stretches out across open country. Depending on the day?s work, you might ride drag at the back of the herd, cover the flank to keep cattle from drifting, or help push from the front as the crew spreads out over rolling rangeland and foothills. Evenings typically include caring for or checking on your horse with the wranglers, sharing stories about the day, and watching the sun drop behind the mountains from camp or the ranch lodge.

Travelers who prefer less riding can often choose shorter horseback sessions or opt for horse?drawn wagon rides, which remain a popular way to experience Montana's landscapes and Western heritage without spending a full day in the saddle. These outings might pair a scenic wagon ride with a cookout, live cowboy music, or interpretive stops at historic and cultural sites, bringing the region?s frontier stories to life for families and groups.

Long days outdoors build an appetite that most ranches meet with hearty, home-style meals - often featuring grilled steaks, fresh salads, baked breads, and classic Dutch-oven sides served in a family-style dining room, at a chuckwagon camp, or under an open tent. After dinner, guests might relax around the fire ring with live Western music, star?gazing, and tall trail tales before turning in; mornings usually begin with the smell of coffee and a hot ranch breakfast as wranglers saddle up for another day on the trail.

For current offerings, dates, and requirements?including age limits, riding experience recommendations, and pricing?visitors should check individual ranch websites or statewide listings of Montana working ranch vacations and cattle-drive experiences.

Updated: January 28,2026